The Scahill 2017 Reel Book

What is this?

In short, I have reinvented a wheel and forgot to improve it.

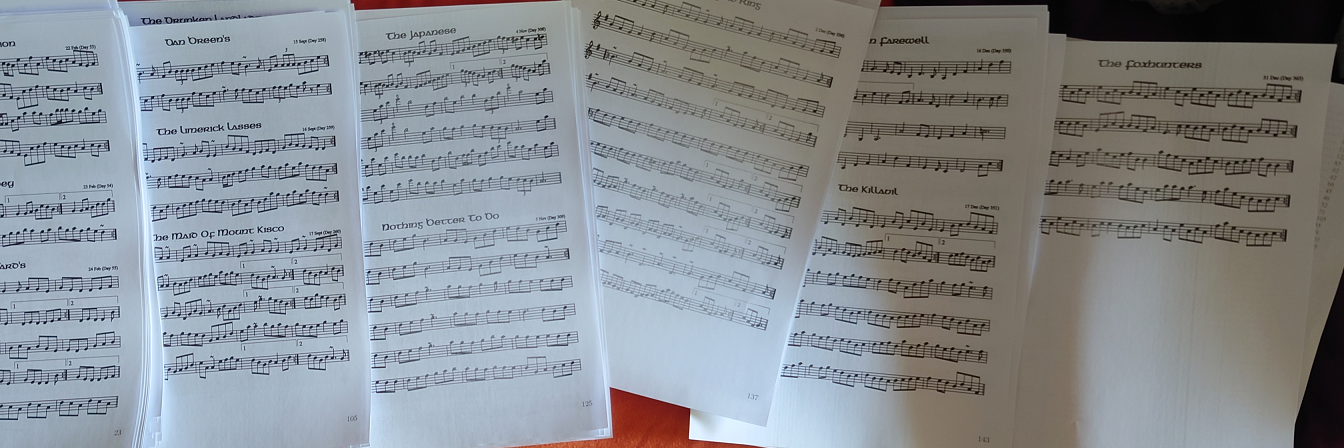

I wrote some tools to help locate and download ABC music notation to use with abcjs (an ABC notation rendering library) and made a Github Pages site for printing every sheet of music (published also in PDF format) from Fergal Scahill’s 366-song Youtube playlist. The process can be generalized to other playlists and instruments:

Vim was used to quickly create a list of song titles, which was input into xargs to search a fiddle sheet music web domain, The Session. The output page was sorted by date and styled to allow multiple songs per page along with an alphabetical index, created later with a short Python script. This project took well over 75 hours—including time needed to learn a few new language constructs, concepts, and libraries; also, for transcribing music from a few recordings.

From the command line, we can navigate immediately to a URL that we want (with decent likelihood) but don’t yet know via a few search engines. The first example targets Firefox and DuckDuckGo. A later solution uses Google. The commands should be generalizable to other browsers and search engines. I expect directly searching via The Session would work, but since I don’t know what costs the server owner would incur and also don’t want to hit some limit and get banned, I chose to use a search engine.

I used pdftk at first to add song info (prepared on individual pages using LaTeX) to each tune after saving directly to PDF from The Session. This tool also could combine multiple tunes per page or create a master book, although the book (created with pdfunite) didn’t use methods to save space, like a single document-wide font. I printed 80 titles to combine in a folder and realized inclusion of a leap day meant all days were off by one. After that, I would need to edit and recompile the LaTeX document and (again) manually typeset multiple tunes onto single pages when there was enough space. I only needed to change or add about 25 tunes, but it was clear that my method did not handle mistakes well.

I wanted a song book that was easy to edit, shareable, and accessible anywhere, and abcjs on a public Github Pages site was my solution.

How is this different from existing tune books?

- searchable

- sortable

- cross-referenced

- fork-ready

- mobile-acquaintancely (It works on my phone.)

- tune difficulty is calculated

In fact, it’s not much different at all! If you look at some existing reference material, you’ll find it to be packed with content in a visually appealing format—sometimes with a hyperlinked index:

- www.capeirish.com/

- www.braccio.me/session.html

- www.braccio.me/oneill/ONeillsMusicOfIreland.pdf

- ifdo.ca/~seymour/ottawaslowjam/

- www.ceolas.org/pub/tunes/tunes.pdf/

- www.vfmc.org.au/VFMClibrary/

- www.joefago.com/tunes-library

- www.mcfc.org.au/s/The-Dutch-Session-Tunebook-2nd-ed.pdf

- www.cheakamus.com/Ceilidh/Downloads/Dows_List.pdf

- www.gulfweb.net/rlwalker/FrancesIrishGroup/FrancesMichaelsIrishGroupTunes/CollectionsOfIrishTunes/

- thereelbook.com

Set lists from The Session are mobile-friendly, searchable, and they are the reference for my tune collection. With some effort, you can create multiple set lists to enforce different sort orders, or you could run a Javascript snippet in the browser console to reorder a saved set list on-the-fly.

Tune difficulty is mostly subjective and really seems linked to a triad of related metrics: tempo, notes per measure, and number of string changes. There’s a penalty for lots of chromatic playing, accidentals, and notes outside of first position. I would consider this mostly an experimental feature, but I suppose perfecting this and making it a standalone feature would be the most novel part of this entire project.

This song collection was built to help with the self-study of fiddle music during the Coronavirus quarantines, but I must recommend to everybody who wants to learn an orchestral string instrument: find a great teacher to keep your posture and habits correct, motivate you, and guide you at your right pace. Personally, I used up all my music lesson money purchasing a decent quality 4/4 violin, and I don’t plan on being concertmaster of any music group that doesn’t want drinking during rehearsals or that won’t fit in my living room.

Lessons Learned

- Compressing a PDF from a website full of a bunch of SVGs is a fool’s errand. This is sad, because a full document of sheet music drawn with vectors should offer plenty of opportunity for compression: make one clef, copy to all staves; make one note head, copy to every note; draw one line, copy to every staff; and so on. It's probably wiser to make one giant ABC document and print using a non-browser-based ABC engraving tool, optimized with a tool like SVGO.

- You can write music quickly with ABC notation, and it doesn’t take an extremely long time to learn. Unlike guitar tabs from the ’90s, ABC converts easily to MIDI or even to notation for specific instruments e.g. mandolin.

- Tune books exist. Tune sites exist. Lots and lots of them. My work was nothing revolutionary: putting a bunch of music together. This whole thing was the result of diving headfirst into a personal project and finding a lot of similar work along the way. Really, it’s a bit like starting a PhD, collecting some data, reading some papers, and realizing some group at POSTECH already did the thing you wanted to do.

- I could have quickly done most of what I wanted with the set list feature on The Session, which will link a bunch of fiddle tunes together on one print-friendly webpage. The UI for creating a set list appears once you have created a user account.

- The longer you look, the more you notice. I think I set out to do something original and eventually reinvented two or three different wheels—and not any better than the existing wheels! In addition to tunebooks, there are many apps, converters, output generators, PDFs/websites with thousands of tunes, and tools to coordinate live sessions and share recordings.

- Some tasks seem like a good idea but are not. Writing down the key signature of each song was one such example, since I rarely looked at this part of my notes while I was trying to find a good setting.

- It’s easy to fall into the trap of adding features, dependencies, complex behaviors, and more. Paradoxically, if you really want to make your own sheet music site, it seems the solution is to go all-in on two libraries: Bootstrap (or a similar jQuery-based library) and abcjs. Most bugs have been ironed out of Bootstrap. Such tasks like creating a date picker widget become a single Javascript command, and jQuery can easily select and modify the (optional) abcjs classes.

- Closely related: Learn to say, “no,” to the to-do list. Between a dedicated to-do list and inline comments to make changes, there were about 70 tasks waiting to be finished at one point in this project. Some became real rabbitholes with little reward.

- Closely related: Do whatever the software equivalent of “measure twice, cut once” is. At one point, I was fighting for hours to get a color gradient on an SVG element using Javascript without jQuery. The case of HTML tags was important but kept getting ignored. Then, I realized it’s so much easier to generate the SVG in advance inside another file and then transfer the output to the main file along with the styling needed for the gradient. In the end, I didn’t use the gradient thing anyway. It was a nice mental exercise but my willpower was weak.

- abcjs is not the best way to typeset music. The output PDF is much larger than other (sometimes larger) sheet music collections. In fact, the page after all scripts are done is more than 40 MB, and an SVG optimizer can halve this size. Also, the strokes are too thick by default. There are definitely missed opportunities to define some vectors once (clefs, markings) and reuse these vectors globally.

- Brother laser printers are great. Printing stopped because the toner cartridge reached its page limit. There is a hidden menu for resetting the cartridge odometer. I was able to get 100 more clean pages before prints began fading. After a handful of faded prints, I paused the job and shook the cartridge, which gave another two dozen decent pages and finished the hard copy of the tune book! To me, since their smaller cartridge should print 1000 pages, this indicates Brother is not too far off on their remaining toner estimate.

- Making a difference matters. This was quite a bit of fun to explore and to make, but I hope it inspires or educates others as it did for me. Feel free to fork, star, or link this project, since the documentation of this project took so much extra time, and I want to know that this time I spent—where I wasn’t with my family or friends or developing my own hobbies or working— was not just a waste.

Background

Learning the fiddle alone can be exhausting—even for an experienced musician!

During a vacation in Ireland, I bought some fiddle sheet music but found that I also needed to know how each song sounds. Even if I play on the piano, I often didn’t know the stylistic differences between hornpipes, jigs, reels, polkas, slides, and slip jigs... It was difficult to find the motivation to practice unless I heard a recording.

While browsing videos, I came across Fergal Scahill’s daily fiddle recordings from 2017. I found these are great because they jump straight into each song at full speed, the audio quality is better than most, and they are almost always played true to style. There is also one song for each day of the year with no songs played twice in one year!

After hearing a few Fergal Scahill recordings, I searched online for more sheet music. This led to The Session, a website with free music in both ABC and staff notation. Many of the songs played by Fergal were available, and they usually were in the correct key or could be copied into an online ABC transposer and added at the bottom of its The Session song page.

This made playing much more interesting and made it easier to form a rehearsal habit. Playing 5 to 15 minutes per night, I always could challenge myself on something: intonation, tempo, timbre, dynamics, flourishes, etc. (Note: Be nice to neighbors: Play with a mute at night.) These daily practice sessions felt productive, efficient, and fun.

Then, the unthinkable happened. A broken USB-C cable fried the charge IC on my laptop. For a variety of reasons, I switched to a desktop. Decent rehearsing had to happen in the room with the computer... unless I printed each song. I share a printer, so rather than print every night—and endure a bit of waste when multiple songs are able to fit on one page—I chose to batch print. After realizing how much collective time this would require, I figured I should share my output so that a handful of other people in the world can benefit and have their own printed version of Scahill’s Fiddle-Tune-a-Day, or what I shall [unoriginally] call, “The (Scahill 2017) Reel Book.”

Getting Titles (vim)

Of the various options for getting titles (YouTube API, copy from source/inspector, copy from view) the most efficient for me is copying the playlist view and getting it into a batchfile-friendly format using vim.

I search for scahill 2017 playlist and select the first result. All titles need to be preloaded by scrolling to the bottom (item 100), waiting for the next 100 results, scrolling to 200, ..., until the full year of titles is displayed. Copy. Open vim.

In vim, type :set paste<Enter>, press i to insert, paste from the clipboard into the terminal, and press <Esc>. (Escape exits the current mode/command. Press it a few times to get back to “normal” mode, where you can then exit vim by typing :q!<Enter> to discard changes or :wq<Enter> to write changes.) After pasting, I have 1831 lines. (Go to EOF by typing G and show line numbers with :set number<Enter>.) As 5 times 366 is 1830, there’s an extra line somewhere. At the file start (gg), every fifth line shows the artist name. We can scroll down to find video 41 was a 360 degree recording. Delete this line (dd).

At this point, you can create a macro to delete everything except the title line and then use small edits plus “visual block mode” to quickly strip away everything except the title. Then, substitution with regular expressions (regex) helps to strip away all non-ASCII characters.

Vim macro ⏱️ 0:02

Go to line one and start recording the macro with qa (which saves to buffer “a”). Line 1 shows the item number, line 2 has the file duration, line 3 has no useful info for me, line 4 has the title, and line 5 has the artist name. This repeats every 5 lines. Since I start on an item number, I want to end the macro on the next item number. I delete lines 1–3 and line 2 (formerly line 5) with dd. With the cursor over the next item number (2), I press q to end the macro recording. Now, typing @a a few times lets me test the macro. Once I see it works nicely, I type 360@a to execute the macro 360 times. Execute the macro until the file has 366 similar lines.

Making block mode work ⏱️ 0:02

Scroll through the file. The first half of each title is almost always identical. We want to change “almost always” to “always”. Things like capitalization don’t matter, but spacing does. To align days 1 thru 9 with the two-digit days, move the cursor so it is directly on the number 1 in “Day 1”, then press <Ctrl>+v and scroll until the single-digit numbers are highlighted. Type I to insert the same input onto each line, insert a space, and press <Esc>. All of the numbers from 1 to 9 should have shifted. Do this again to align 1–99 with the three-digit numbers after checking everything is properly aligned. For me, Day 73 needs the year (or some placeholder text) before the text “Day 73”. To insert, press i, type the text, press <Esc>. (Undo with u. Instead of repeatedly scrolling, you can also press 98<Down> to jump from number 1 to number 99.)

Small edits need to be made so the titles are spaced consistently. Days needing extra spaces for proper alignment include 11, 18, 81, 104, 111, 116, 141, 209, 212, 217, 219, 228, 233, 234, 236 to 239, 242, 243, 246, 247, 249, 251, 265, 270, 284, 292 to 306, 308 to 317, 319 to 358, and 360 to 363. (It’s not important if there is a dash or exclamation mark or space or other symbol; they will all be deleted soon.) A few days are missing their title completely: 103, 109, and 123. These titles are in the video description and should be added. (a inserts after the cursor position, which is more useful than i here.) Day 177 could be deleted as it is a repeat title, although I believe it’s a repeat of Day 25, which might have the wrong title. For now, I would keep it. If it turns out there is an extra day (no repeats), it can become a leap day title. However, maybe move the original Day 177 to the end? (Select it and type ddGp. This is a mix of two earlier commands plus p to paste the last deleted line after the current line.) As quite a few of these songs are appropriate for a specific day of the year, it makes sense to disallow an extra song in the middle of the playlist and to deal with leap days separately. Day 318 has “Day Day” instead of “Day”. Pressing x will delete a single character. Delete the extra text on day 177. Days 96, 115, and 118 repeat the day number in the title, so delete that. Day 213 has extra text in the title. Maybe there’s more?

With everything properly aligned, you can block delete everything except the titles. Go to the beginning of line 1 (gg) and start a block selection (<Ctrl>+v). Jump to the bottom line (G) and either move the block manually (<Right> until the last selected column of the block is the space before the titles) or skip ahead by typing f- (or f! for Day 365) a few times to find the first instance of the next typed character. After the block is selected, press x to delete.

Replacing or removing non-ASCII characters ⏱️ 0:01

While Unicode is a great idea, it works against us here. We want to paste each line into the address bar of a web browser using a batch file. Simple characters usually don’t need to be escaped (like when the slash character, / is represented by %2F in URLs or \/ in a vim search), and it doesn’t get much simpler than ASCII. In fact, I would substituted everything except letters, numbers, and spaces. Let the search engine figure out apostrophes and hyphens!

Rather than explaining how substitution works from the very beginning, I’ll list the commands (type : yourself instead of pasting and press <Enter> after each command):

:%s/[[=a=]]/a/g

:%s/[[=e=]]/e/g

:%s/[[=i=]]/i/g

:%s/[[=o=]]/o/g

:%s/[[=u=]]/u/g

:%s/[^a-z 0-9]//g

:%s/\<./\u&/g

If you’re unfamiliar with vim regex: Note the similarities from line to line. The colon character starts a vim command. The percent symbol applies each command to the entire file. Character s indicates a substitution, and the ending g applies this substitution globally (as many times as needed per line). The slashes surround two terms: the term to find, and the term to replace. For the vowels, the find term looks for any text character that is based on a specific vowel, so an accented a is based on the standard, non-accented a. The sixth line looks for any character that is not a letter, a space, or a number, then replaces all of these with nothing. (That is, they are deleted.) The final substitution finds the first character per word and replaces it with the same character in uppercase.

This assumes your vim configuration ignores case. It also will change the capitalization of some titles and delete some characters that improve readability e.g. hyphens. The final line will capitalize the first letter of every word, and you will now have a text file with each approximate title.

Finding Search Results on a Specific Domain

In this case: finding song notation on The Session.

The trick here is to create a batch file for a specific OS and shell to open a web browser on the user’s computer that supports flags to jump immediately to a URL of any number of search engines that redirect to the first search result. We must also make sure the titles are properly escaped for both the executable argument as well as the search engine. It seems the current URL to immediately redirect on DuckDuckGo is https://duckduckgo.com/?q=!+site%3Athesession.org+ where the desired search query is inserted after the last +. Some engines (Google) will not always provide the redirect URL even when explicitly requested.

xargs is a command on most Linux/Unix-like systems which will run a command on each line of an input file. I usually start with xargs by creating a sample input and echoing the output command, since the command options do not provide this exact functionality.

On Firefox:

firefox -new-tab <url>

Using xargs:

xargs -l echo firefox -new-tab https://duckduckgo.com/?q=!+site%3Athesession.org+ < sample.txt

If each line looks like a valid command, try copying and pasting the first result

and checking what happens. If the tab opens to a song page on thesession.org,

then it’s probably time to expand the script to accept the full input. Be

mindful that each search engine probably limits results via throttling (10 to 20

pages per 30 to 120 seconds), manual verification by a human (CAPTCHA), or some

other anti-bot mechanism. To avoid these sorts of issues, most shells would

have commands to wait a specified duration or to pause until a key is pressed.

This code (to open 16 tabs at a time with a 69 second delay before the next 16) will fail:

xargs -P 16 -I @ sh -c '{ firefox -new-tab https://duckduckgo.com/?q=!+site%3Athesession.org+@; sleep 69; }' < scahill.txt

The reason the command above fails is that nearly every title has a space.

Running the first echoed output illustrates this point. For Linux, the metaphorical

card to insert into your house of cards above is the tr command, which

substitutes each instance of a single character with another single character.

cat scahill.txt | tr ' ' + | xargs -P 16 -I @ sh -c '{ firefox -new-tab https://duckduckgo.com/?q=!+site%3Athesession.org+@; sleep 69; }'

To start from a specific line, put between cat and tr:

tail -n +<line nr>

Frustration (while batch opening search engine tabs) ⏱️ 2:00

To get an ABC file for each song, each song’s tab has to be opened, and this just takes time.Tools that didn’t work great:

- DuckDuckGo (understandably) will block HTTP requests from your IP address if you exceed their rate limiter.

- Google’s I’m Feeling Lucky

buttonURL usually does not work. - curl didn’t follow the I’m Feeling Lucky redirect when the [seemingly] appropriate flags were set.

- Google will give you an anti-bot prompt after a hundred requests or so. No big deal. Watch the favicons to catch it. If you don’t do the first few right away, they (reCAPTCHAs) become more aggressive.

- Changing Firefox’s referer/referrer/origin heading settings doesn’t seem to change Google’s redirect behavior.

- Firefox would sometimes freeze (Fedora/GNOME/Wayland/Nvidia/32G RAM). Quit + Restore is not the solution. Opening a new firefox process will unfreeze the other processes.

A tangent on that last point: If you ever witness a passionate discussion about the merits and drawbacks of Wayland, rest assured everyone taking part in the discussion is a giant idiot (me, too—for taking a stance) and that the actual solution to the X11 problem is that someone very charismatic and competent needs to take charge of the future of Linux. It is possible for both sides of an argument to be wrong, and that’s how I could best describe the 2022 status of Wayland in a dozen words.

What seemed to work?

cat scahill.txt | tr ' ' + | xargs -P 10 -I @ sh -c '{ firefox -new-tab https://google.com/?btnI=I%27m+Feeling+Lucky\&q=@; sleep 120; }'

These piped commands would load Google’s front page with the query input pre-populated and the cursor at the beginning of each query. I only need to switch from tab to tab, pasting “site:thesession.org” and pressing I’m Feeling Lucky before advancing to the next tab. This takes less than 2 seconds per tab, and I can use the other 90 seconds to check the results with alternate titles. (It’s also likely I could have used a much smaller timeout, as Google’s front page doesn’t seem to be heavily rate limited.)

Linking directly to search results from The Session would probably also work, but it seems like a dick move as the site seems to be maintained by one developer who relies on visitor donations. Plus, I’m not sure if there’s a way to go directly to the first search result using the site’s URL.

Also, at this stage we find some title misspellings: boa should be boat, dongeal should be donegal, caliope is calliope, etc. Some matter, others don’t. (Google usually will still land on the correct result.) Some tunes are written by Scahill or his friends and family, so they do not have a listing on The Session. (If I have time, I might change that by typing out the ABC and submitting it to The Session.)

After about an hour, we have over 300 tabs open. If I were more knowledgeable in Firefox’s file structure, I would back up my session data and simply strip the URLs from the session data file. Most important at this moment? Getting each URL into a spreadsheet in case Firefox or anything else goes kaput. This is about the length I would decide can be done manually just barely quicker than with automation. (If I knew a vim-macro-like method of clicking through pages, I would use that. I know about Selenium, but then I would need to learn Selenium. So far, I haven’t needed to do enough web-based automation to justify the time needed to learn.)

The end result of this work is an in-progress spreadsheet with dates, titles, styles, and URL made using Google Drive and exported as HTML. There are columns already defined so I can do a supervised, automated analysis of each song’s characteristics and estimated difficulty.

ABC Music Notation

At this point, I wanted to find pieces that were closest to what Fergal Scahill played as well as rate each song’s difficulty as played.

Key (Pitch) ⏱️ 3:00

In short, writing down each key was a waste of time.

I tried looking for existing tools to determine the key of each song. The best I could find was https://youtubekeyfinder.com, but after waiting a full song duration, the load indicator was still moving for the example I selected. Other tools exist but need access to an audio file, and I’m not inspired to reinstall youtube-dl. Instead, this is one area where manual work is actually probably the best way forward. (I later discovered you might be able to stream audio into librosa and do semi-automatic key detection.)

With my fiddle placed on the table near me, I’ll jump immediately into each song by pressing 3 or 4, which jumps to the 30% or 40% mark, respectively. As most of Fergal’s songs are in G, D, or A—or the minor equivalents: Emin, Bmin, F#min —I should only need to pluck a few open strings in most cases. Then, write down the key and press N to advance to the next song in the playlist. Napkin math finds this will probably take 2 to 4 hours. It’s pretty close, in my opinion, to the time it would take to download open-source tools and configure everything correctly to do the job via automation.

One nice thing? Key is an easy-to-find feature of ABC notation. It’s in the header. This narrows down the tunes I need to check to those with the correct key. This, of course, relies on the reported key being correct and matching what I heard.

One downside? Irish music seems to be diverse in mode. I found plenty of examples of Ionian (major), Dorian, Mixolydian, and Aeolian (pure minor). Since the order of half steps and full steps is the same in all four cases, it’s not so easy to say, “oh, that key has one sharp. It’s probably in the key of G,” since this can also indicate E minor, A Dorian, or D Mixolydian. (I think those are correct.) There were even a few melodic minor songs, some that changed key, and one or two that didn’t have an entry on The Session as they need an unsupported key e.g. Bbmaj.

Another annoyance is the title Paddy Fahey’s, which refers to 40+ different tunes by Paddy Fahey, a famous fiddler who never really recorded or published his songs.

Tempo ⏱️ 2:30

At this point, I started to think in terms of how long a single task will take. I would need one hour to complete a given task per every 10 seconds each song needs. I wanted to get the tempo that Fergal Scahill plays each song, and I estimate that will take 20 seconds per song. I used an Android app called Metronomerous, which is free and has no advertising. (If you use and like it, there’s a supporter edition as well as a website with a donation link. There’s a feature to tap a few times and quickly get the current tempo within a few beats per minute (BPM).

Most of the tempi were similar within a specific style. For instance, most of the jigs were performed close to 128 BPM. Hornpipes and barndances were usually played near 200 BPM. Reels often skipped along at 220–240, although a decent amount were noticeably faster (275) or slower (125).

create histogram of tempos by rhythm type

Copying ABC from The Session to Github ⏱️ 13:00

The goal is to minimize time needed on purely repetitive tasks. To that end, I

opened a unique file for each song at once using vim and set up paste mode:

vim -- $(seq -w 365 | sed 's/^\(.\)*/abc\0.txt/')

seq creates a counting sequence, sed edits this stream of numbers using a regular expression substitution (similar to those used on this page for ASCII manipulation in vim). :n<Enter> goes to the next file in vim. The first file, abc001.txt will be open for editing with the other 364 files open in the background—but not yet saved to disk.

With Youtube open in a window at screen left and The Session tabs open in a window at screen right, I played each video and then played an audio sample from each The Session abcjs player. When one of the abcjs files sounded correct, I opened the ABC view tab for that setting. Otherwise, I scrolled to the bottom of the page to show that a specific song would need more manual work. I did this in batches of maybe ten to twenty songs.

When I realized it would take longer to switch between vim and Firefox than to simply use Github’s file editor, I pushed all filenames to Github and then opened each file in its own tab. This is where I wish vim macros could be used outside of vim or you could select a block of text on a webpage, right click, and select Open every link in the selected text in a new tab. (It is possible to do this in Google Sheets, but one must balance the initial setup time against simply clicking each link.)

Adding each month’s tunes seemed to take about one hour. This time was mostly used for choosing the correct variation from many similar options, transposing an existing setting into our desired key, or finding the corrected URL to a title—which often involved a different name or searching with a snippet of music notes, which is a cool feature of The Session once you are comfortable with ABC notation.

Predictably, the 80–20 rule applied. The majority of time was spent troubleshooting a minority of tunes.

Usually, a tune really needed about 30 or 40 seconds to process: jump into Scahill’s part on Youtube for a few seconds, play the MIDI-like audio from The Session for a few measures, declare a match, copy, paste, and save.

Near the halfway point, I noticed in a dark corner of The Session that there is a web app for identifying a tune based on a played melody. Pretty cool stuff!

Creating ABC content by ear ⏱️ 4:00

Some songs needed to be typed manually because a setting didn’t exist. In these cases, I needed to pick up an instrument, set the Youtube speed to 0.5, and pluck out notes to type out in ABC format. I had to look at the ABC standard often, which probably took the majority of time e.g. figuring out how to write notes, define tempo, add space, remove clefs, slur and tie notes, and so much more.

Each setting could be verified with the instant audio output provided by abcjs.net.

The exceptionally challenging piece to transpose was Marry Me of a Monday, which took roughly two hours because of double stops, chords, slight variations between repeats, and some sustained note lengths. It did help that the tempo was extremely consistent. I used librosa to help, which took a bit of time to set up but proved to be a powerful library and a helpful transcribing tool using the constant-Q transform display.

Difficulty Ranking ⏱️ 0:00

TODO: timeAn algorithm for difficulty was written after every song was in a Git repository, since this was the quickest way to have a script analyze each tune. To figure out difficulty, I considered a handful of metrics like number of notes played in a given duration, number of string changes, variety of note lengths, etc. Fortunately, much of this can be gleaned from the ABC file itself and a well-written Python script. Then, I manually figured a difficulty level for a small selection of tunes as a sort of training set.

TODO: content

Output

The results of this project are nothing special. They don’t advance the state of the art, but that doesn’t make the process less fun. (Most woodworkers aren’t inventing new types of furniture. Most cooks are cooking well-established recipes. This was coding slightly outside my comfort zone in order to typeset music—where others have made great progress.) I was able to make a fairly compact yet readable catalog of music to help me learn and enjoy my fledgling hobby. I learned a lot about ABC notation and would probably use that often in the future—for trombone arrangements and maybe even for writing ensemble scores. The unseen work includes the arrangements I created for this book and the settings I submitted to The Session.

I also experimented quite a bit with a Python audio/music library, librosa, which is super cool as it does beat detection, displays dominant musical pitches for every note, separates streams based on frequency content (percussion, vocals, backing), automatically segments songs (e.g. ABABCCDB), stretches audio, shifts pitch, synchronizes time warped music, mu-law compresses/expands, detects intonation, and so much more! It also uses Python generators, so some analysis functions can be performed on streams and large files.

Really, this is the sort of project that would have been nice for the PennApps hackathon (or any college hackathon) since it provides good exposure to a variety of libraries, has tasks that are easily separable by skill/interest, can be accomplished (to varying degrees) by a team in less than ten hours, and exposes many techniques and tools that would make this sort of work faster in the future. Over the course of this project, I was able to generate dozens of tasks and stretch goals. A team of four motivated students could tackle many of these goals in an intense weekend and even try ridiculous tasks like applying machine learning to the entire database of The Session tunes (by type) to create a David Cope-esque fiddle tune classifier/generator. Web developers can try creating a global SVG gradient, and this project can involve loads of AJAX and network optimization and use of The Session’s API. One could even submit pull requests to abcjs, as a few times I noticed areas where the standard is clear but the implementation could be improved, such as note ties inside of chords or unimplemented directives. This sort of work could be the basis for a marching band music app that works on tablets and phones and automatically synchronizes between players.

(Penn Band wanted this, and I recall licensing cost being the biggest hurdle. Developing your own tool gets rid of the software costs. Sadly, most music publishers are unlikely to permit the conversion of licensed sheet music to a digital format for displaying without charging an extra fee, e.g. a Digital Derivative Visual Representation (DDVR) license. This is a damn shame, because this conversion to digital is what a modern copy machine does—albeit temporarily. Somehow, having a screen instead of paper makes the music more valuable?)

Making a print-friendly page ⏱️ 5:00

It took about an hour to find a good example of generating an array of divs with three digit numbers as part of each id for abcjs to populate, and most of this time was determining the order to load each script. There is probably a really great, consistent, cross-browser method of doing this. My solution was to move things around and add defer or change the script loading moment for each script until things started to work.

It then took about 3 hours to figure out how to asynchronously load from files into variables and load those variables using abcjs to replace the div contents. The filenames and div IDs are generated using for-loops, and missing files should be handled correctly on Github Pages.

Creating a print stylesheet and selectively hiding elements took another hour or so.

It took about 30 minutes to create a Table of Contents manually, and much of this time was for stripping away nonalphanumeric characters and removing leading articles (the, an, a) before sorting, as well as some time for typesetting in LibreOffice. The Python code for sorting is part of the Github repository.

Documenting Everything ⏱️ 20:00

Typing each step seemed to double the overall duration of the project, although it also is a good exercise in keeping thoughts and efforts organized, and I also learned more about using Bootstrap, Webfonts, Javascript, preloading external web sources, ABC notation, and other minor tools. To save space, reduce complexity, and improve performance, unnecessary CSS was stripped away with Chrome. CSS tweaking took longer than expected; Google Pages needs 20 to 90 seconds to copy a commit onto the webserver. If this were a larger project, I would host it locally and upload all at once after major revisions.

A lot of time was also taken to get minor details right on my computer, mobile browser, and printer. This really added several hours, and I’m unlikely to make further changes to support other configurations unless there’s a lot of interest. I occasionally would read the entire document and try to rewrite as clearly as possible, adding about two hours to the clock. A few minor diversions, like drawing a piano keyboard in SVG, are included in this section, but these took probably less than one hour overall.

Little details ≠ Easy details ⏱️ 20:00

Many page improvements, such as tests and implementation of jQuery sort methods, were not detailed here but still cumulatively took a substantial length of time. For the most granularity/details, look at the todo1.md checklist from the website repository or the changelog itself (although not every commit message was as detailed or descriptive as I had wished). I lost track of editing time (for instance, typesetting each song) somewhere near a total project duration of about 100 hours. This is also around the time where documentation consisted essentially only in commit log messages. Additionally, the longer the typesetting task lasted, the more automation I would add. If I noticed I was typing the same commands in vim, I would map those commands to a function key or create a macro.